Laurent Millet (born in 1968) is a French photographer and visual artist known for blending photography with sculpture, drawing, and installation. Rather than documenting the world directly, he constructs objects, architectural forms, and poetic “machines” that he places in natural or studio environments before photographing them. His work explores the boundary between reality and representation, and the interplay between volume, space, and surface.

Millet often uses historical or handcrafted photographic processes—such as ambrotype, cyanotype, salted paper prints, or gelatin silver prints—giving his images a timeless, material quality.

He has received several major distinctions, including the Nadar Prize (2014) for his book Les Enfantillages Pittoresques and the Niépce Prize (2015). His work has been exhibited widely in France and internationally, and is held in collections such as the Bibliothèque nationale de France and the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature.

Millet lives and works in La Rochelle and teaches at the École supérieure d’art et de design TALM in Angers.

About l'Astrophile serie:

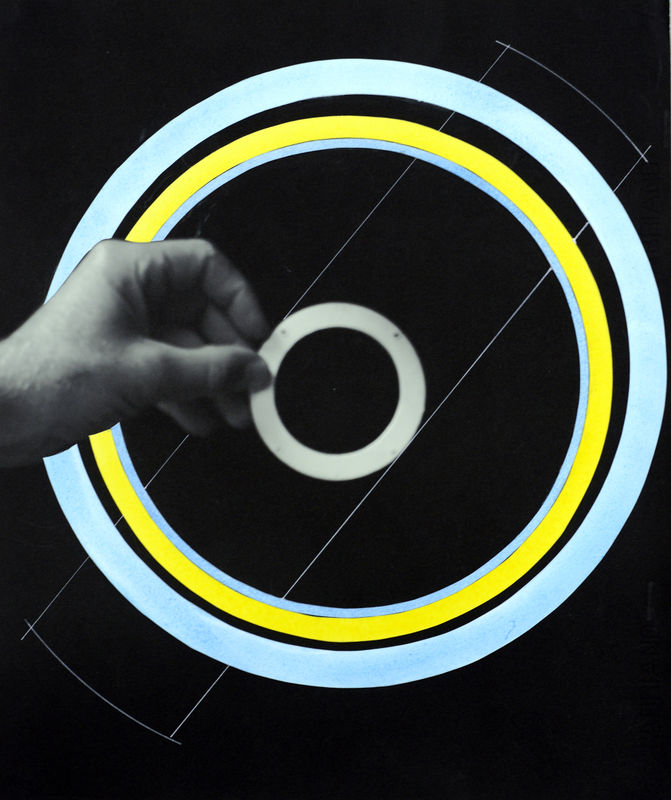

L’Astrophile is a photographic series in which Laurent Millet constructs enigmatic, pseudo-scientific objects—structures reminiscent of observatories, measuring instruments, or fragments of imaginary architectures—and situates them in sparse landscapes or minimal studio settings. These invented devices belong to the artist’s wider “imaginary encyclopedia,” a constellation of speculative machines and hypotheses that photography renders tangible.

A profound resonance runs between this series and Johannes Kepler’s Somnium (The Dream, 1608/1634), often considered the first true work of science-fiction. In Somnium, Kepler stages a dream-journey to the Moon in order to explore astronomical ideas that could not, at the time, be expressed directly without risking theological or political backlash. The text mixes scientific reasoning, imaginative speculation, and narrative allegory—a hybrid form that mirrors Millet’s own method: using fiction to reveal truths, and using constructed forms to explore the limits of knowledge.

Like Kepler, Millet creates a space in which scientific inquiry becomes inseparable from poetic invention. His objects recall instruments of observation, yet their purpose remains opaque; they seem to measure something indeterminate, as though they belong to a science not yet discovered. In this way, L’Astrophile operates much like Kepler’s dream-narrative: it proposes a world where empirical curiosity, speculation, and metaphor coexist, and where the tools of understanding are themselves ambiguous.

The landscapes in which Millet places his constructions echo the desolate, extraterrestrial terrains imagined in Somnium. They function as liminal zones—neither earthly nor fully other—suggesting a threshold between reality and speculation. The viewer becomes a kind of traveller or dreamer, encountering instruments whose meanings must be deduced, invented, or intuited.

Millet’s use of historical photographic processes deepens this connection. Just as Kepler blended contemporary scientific knowledge with an archaic, dreamlike narrative form, Millet mixes modern artistic inquiry with techniques that evoke early scientific illustration and astronomical observation. The resulting images feel both ancient and futuristic—timeless artifacts from a parallel history of science.

Through this dialogue with Somnium, L’Astrophile becomes more than a study of objects; it becomes an inquiry into how humans imagine the cosmos, construct knowledge, and build fragile devices to reach beyond themselves. Millet’s images, like Kepler’s dream, remind us that the pursuit of understanding often begins not with certainty, but with wonder.